Strömgren sphere

In theoretical astrophysics, there can be a sphere of ionized hydrogen (H II) around a young star of the spectral classes O or B. The theory was derived by Bengt Strömgren in 1937 and later named Strömgren sphere after him. The Rosette Nebula is the most prominent example of this type of emission nebula from the H II-regions.

Contents |

The physics

Very hot stars of the spectral class O or B emit very energetic radiation, especially ultraviolet radiation, which is able to ionize the neutral hydrogen (H I) of the surrounding interstellar medium, so that hydrogen atoms lose their single electrons. This state of hydrogen is called H II. After a while, free electrons recombine with those hydrogen ions. Energy is re-emitted, not as a single photon, but rather as a series of photons of lesser energy. The photons lose energy as they travel outward from the star's surface, and are not energetic enough to again contribute to ionization. Otherwise, the entire interstellar medium would be ionized. A Strömgren sphere is the theoretical construct which describes the ionized regions.

The model

In its first and simplest form, derived by the Danish astrophysicist Bengt Strömgren in 1939, the model examines the effects of the electromagnetic radiation of a single star (or a tight cluster of similar stars) of a given surface temperature and luminosity on the surrounding interstellar medium of a given density. To simplify calculations, the interstellar medium is taken to be homogeneous and consisting entirely of hydrogen.

The formula derived by Strömgren describes the relationship between the luminosity and temperature of the exciting star on the one hand, and the density of the surrounding hydrogen gas on the other. Using it, the size of the idealized ionized region can be calculated as the Strömgren radius. Strömgren's model also shows that there is a very sharp cut-off of the degree of ionization at the edge of the Strömgren sphere. This is caused by the fact that the transition region between gas that is highly ionized and neutral hydrogen is very narrow, compared to the overall size of the Strömgren sphere.[1]

The above-mentioned relationships are as follows:

-

- The hotter and more luminous the exciting star, the larger the Strömgren sphere.

- The denser the surrounding hydrogen gas, the smaller the Strömgren sphere.

In Strömgren's model, the sphere now named Strömgren's sphere is made almost exclusively of free protons and electrons. A very small amount of hydrogen atoms appear at a density that increases nearly exponentially toward the surface. Outside the sphere, radiation of the atoms' frequencies cools the gas strongly, so that it appears as a thin region in which the radiation emitted by the star is strongly absorbed by the atoms which loose their energy by radiation in all directions. Thus a Strömgren system appears as a bright star surrounded by a less-emitting and difficult to observe globe.

Strömgren did not know Einstein's theory of optical coherence. The density of excited hydrogen is low, but the paths may be long, so that the hypothesis of a super-radiance and other effects observed using lasers must be tested. A supposed super-radiant Strömgren's shell emits space-coherent, time-incoherent beams in the direction for which the path in excited hydrogen is maximal, that is, tangential to the sphere.

In Strömgren's explanations, the shell absorbs only the resonant lines of hydrogen, so that the available energy is low. Assuming that the star is a supernova, the radiance of the light it emits corresponds (by Planck's law) to a temperature of several hundreds of kelvins, so that several frequencies may combine to produce the resonance frequencies of hydrogen atoms. Thus, almost all light emitted by the star is absorbed, and almost all energy radiated by the star amplifies the tangent, super-radiant rays.

The Necklace Nebula is a beautiful Strömgren's sphere. It shows a dotted circle which gives its name. The dots correspond to a competition of the modes emitted by the Strömgren's shell. The star inside is too weak to be observed.

In supernova remnant 1987A, the Strömgren shell is strangulated into an hourglass whose limbs are like three pearl necklaces.

Both Strömgren's original model and the one modified by McCullough do not take into account the effects of dust, clumpiness, multiple stars, detailed radiative transfer, or dynamical effects.[2]

The history

In 1938 the American astronomers Otto Struve and Chris T. Elvey published their observations of emission nebulae in the constellations Cygnus and Cepheus, most of which are not concentrated toward individual bright stars (in contrast to planetary nebulae). They suggested the UV radiation of the O- and B-stars to be the required energy source.[3]

In 1939 Bengt Strömgren took up the problem of the ionization and excitation of the interstellar hydrogen.[1] This is the paper identified with the concept of the Strömgren sphere. It draws, however, on his earlier similar efforts published in 1937.[4]

In 2000 Peter R. McCullough published a modified model allowing for an evacuated, spherical cavity either centered on the star or with the star displaced with respect to the evacuated cavity. Such cavities might be created by stellar winds and supernovae. The resulting images more closely resemble many actual H II-regions than the original model.[2]

The mathematics

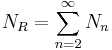

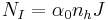

Let's suppose the region is exactly spherical, fully ionized (x=1), and composed only of hydrogen, so that the numerical density of protons equals the density of electrons ( ). Then the Strömgren radius will be the region where the recombination rate equals the ionization rate. We will consider the recombination rate

). Then the Strömgren radius will be the region where the recombination rate equals the ionization rate. We will consider the recombination rate  of all energy levels, which is

of all energy levels, which is

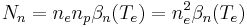

is the recombination rate of the n-th energy level. The reason we have excluded n=1 is that if an electron recombines directly to the ground level, the hydrogen atom will release another photon capable of ionizing up from the ground level. This is important, as the electric dipole mechanism always makes the ionization up from the ground level, so we exclude n=1 to add these ionizing field effects. Now, the recombination rate of a particular energy level

is the recombination rate of the n-th energy level. The reason we have excluded n=1 is that if an electron recombines directly to the ground level, the hydrogen atom will release another photon capable of ionizing up from the ground level. This is important, as the electric dipole mechanism always makes the ionization up from the ground level, so we exclude n=1 to add these ionizing field effects. Now, the recombination rate of a particular energy level  is (with

is (with  ):

):

where  is the recombination coefficient of the nth energy level in a unitary volume at a temperature

is the recombination coefficient of the nth energy level in a unitary volume at a temperature  , which is the temperature of the electrons and is usually the same as the sphere. So after doing the sum, we arrive at:

, which is the temperature of the electrons and is usually the same as the sphere. So after doing the sum, we arrive at:

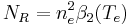

where  is the total recombination rate and has an approximate value of:

is the total recombination rate and has an approximate value of:

![\beta_2(T_e) \approx 2 \times 10^{-16} T_e^{-3/4} \ \mathrm{[m^{3} s^{-1}]}](/2012-wikipedia_en_all_nopic_01_2012/I/eeae59bf7ecc9ecd94df6d7354b74a49.png) .

.

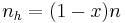

Using  as the number of nucleons (in this case, protons), we can introduce the degree of ionization

as the number of nucleons (in this case, protons), we can introduce the degree of ionization  so

so  , and the numerical density of neutral hydrogen is

, and the numerical density of neutral hydrogen is  . With a cross section

. With a cross section  (which has units of area) and the number of ionizing photons per area per second

(which has units of area) and the number of ionizing photons per area per second  , the ionization rate

, the ionization rate  is:

is:

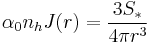

For simplicity we will consider only the geometric effects on  as we get further from the ionizing source (a source of flux

as we get further from the ionizing source (a source of flux  ), so we have an inverse square law:

), so we have an inverse square law:

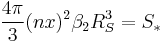

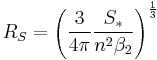

We are now in position to calculate the Stromgren Radius  from the balance between the recombination and ionization

from the balance between the recombination and ionization

and finally, remembering that the region is considered as fully ionized (x=1):

This is the radius of a region ionized by a type O-B star.

References

- ^ a b Strömgren, Bengt. (1939). "The Physical State of Interstellar Hydrogen". The Astrophysical Journal 89: 526–547. Bibcode 1939ApJ....89..526S. doi:10.1086/144074.

- ^ a b McCullough Peter R. (2000). "Modified Strömgren Sphere". Publications of the Astronomical Society of the Pacific 112 (778): 1542–1548. Bibcode 2000PASP..112.1542M. doi:10.1086/317718.

- ^ Struve Otto, Elvey Chris T. (1938). "Emission Nebulosities in Cygnus and Cepheus". The Astrophysical Journal 88: 364–368. Bibcode 1938ApJ....88..364S. doi:10.1086/143992.

- ^ Kuiper Gerard P., Struve Otto, Strömgren Bengt (1937). "The Interpretation of ε Aurigae". The Astrophysical Journal 86: 570–612. Bibcode 1937ApJ....86..570K. doi:10.1086/143888. http://adsabs.harvard.edu/cgi-bin/nph-bib_query?bibcode=1937ApJ....86..570.